Embracing Complexity

The CALI methodology as a path towards Adaptive Management in complex settings

The case study below looks at UNDP’s development and application of the Causality Assessment for Landscape Interventions (CALI), a learning and adaptive management tool designed to support interventions aimed at reducing deforestation in complex settings.

The case provides the rationale behind the development of the tool, its methodology, and the learnings from the process of applying CALI in the Peruvian Amazon.

Illustrations: Ivana Čobejová

The approach has several distinguished features:

1

It builds on systems mapping as a tool for impact assessment. A systems map is built with the representatives of key landscape stakeholders and is used to reflect on the effectiveness of a suite of interventions. This allows stakeholders to put the system that drives the outcomes of interest (in this case, deforestation) at the center of the assessment.

2

It is a highly participatory approach and relies on the perceptions – and collective sensemaking – of the participants to interpretate data and assess whether positive change is materializing in the system. And whether and which contributions were – or can still be – made.

3

It is action-focused, as it builds on these insights to propose actionable recommendations for adaptive management.

4

Finally, it contributes to systems learning, as it encourages the participants to think in systems, and understand the relationships and feedback loops between the structures and patterns that shape the behavior of a system, and their role in it.

After a short introduction, the case study covers:

- What is CALI?

- How does it work?

- Implementation of CALI in Peru

- Learnings from the field

- Must-have mindsets

- Conclusions

The Centre for Public Impact has helped produce this study and we thank them for their insights and excellent collaboration. We also extend a great thanks to the CALI facilitators, as well as the staff and partners of the “Sustainable Productive Landscapes in the Peruvian Amazon” project for sharing their journey and learning with us. We hope you find this case study interesting and useful, and we hope that you’ll stay tuned for the next pieces in this series.

Introduction

Monitoring, Learning, and Evaluation (MLE) should not be a static field; it must be an ever-evolving discipline, constantly adapting to meet the complex challenges of our time. In a context of continuous and rapid transformations, methodologies such as the Causality Assessment for Landscape Intervention (CALI) have the potential to support development practitioners and organizations aiming to design and implement transformative initiatives in a more agile, effective, and responsive way to complex and ever-changing settings.

Since we live in realities that are shaped by the interaction of several nested systems, each with its own inherent complex dynamics, it is critically important for development practitioners and organizations to have access to tools and practices to support them to continuously learn and adapt effectively. The most optimal way to inform this adaptation is through enabling complexity-aware sensemaking processes. This is where the CALI methodology finds its stride.

What is CALI?

The “Causality Assessment for Landscapes Intervention” (CALI) is a methodology that “supports adaptive management through promoting continuous, participatory reflection on the effectiveness of project interventions in reducing deforestation at landscape or jurisdictional level.” This adaptive approach is especially useful for teams who work in systems in complex and or rapidly changing contexts. CALI was conceived by the collaborative efforts of the United Nations Development Programme Food and Agricultural Commodity Systems (UNDP FACS) team and the Good Growth Partnership (GGP) projects in Liberia, Indonesia, and Paraguay. It provides landscape and jurisdictional approaches (LJA) project teams with a practical methodology to explore causality along their impact pathways with a systems lens, including through engaging in deep conversations with landscape stakeholders.

CALI operates by fostering collaborative discussions among key stakeholders in the local landscape. These discussions focus on exploring the project's theory of change, dissecting causality, and scrutinizing the validity of foundational assumptions. Throughout this process, the intricate context of the complex system fueling deforestation in the landscape remains a central consideration.

How does it work?

The CALI methodology is composed of 5 key steps, which are presented below. Teams are encouraged to engage with the methodology at least 2 times during a programme or project lifecycle: at the outset and midway through, to ensure implementing teams have the adequate time to react to the insights they gain through the process. Implementing teams are recommended to onboard experienced System Mapping and adaptive management facilitators to support the process. The following steps apply to every application of CALI, with minor variations depending on whether it is the first or a subsequent iteration, and on the timing of implementation.

Step 1: Preparation

A CALI project manager must be appointed and tasked with developing an implementation plan that outlines the time and resources required to implement the methodology to adapt the project Theory of Change (ToC) in real time. Many inputs must be retrieved or prepared, including project monitoring data and a thorough stakeholder analysis.

Step 2: Initial System Map:

Project teams ought to collaborate with community partners to develop a System Map, thereby deepening their comprehension of the intricate system dynamics causing deforestation in the designated landscape. External facilitators can support the team to develop a physical and digital map leveraging a range of participatory methods.

Step 3: Identify Project Impact Areas within the System Map:

Through this step, the project team and key stakeholders will start making sense of the project’s existing theory of change (ToC) considering the broader system/s driving deforestation at the landscape or jurisdictional level. This will allow them to identify any blind sports, while reviewing key project assumptions.

Step 4: Review Project Impact Pathways:

After having situated the ToC of the project within the broader system/s driving deforestation at landscape or jurisdictional level, the project team will engage in a question-based, participatory causality assessment to review their interventions and impact pathways together with key landscape stakeholders. This will allow them to identify any gaps and opportunities to strengthen implementation and come up with concrete

Step 5: Refine the Project’s ToC, suite of interventions and results framework

Lastly, the team should leverage insights from the previous activities to adapt the theory of change, implementation strategy and results framework of the project.

For a deeper understanding of how to effectively implement this methodology, practitioners are encouraged to consult the CALI Guidebook. 📜

🔎 A case in point: implementation of CALI in support of the Sustainable Productive Landscapes project in Peru

The Global Environment Facility (GEF) funded Sustainable Productive Landscapes in the Peruvian Amazon project was initiated in 2018 as a mechanism to “promote sustainable production systems free of deforestation to generate multiple environmental benefits.” It is a joint initiative of UNDP with the Peruvian government and local authorities to protect a critical ecosystem, while safeguarding and enhancing the customs and livelihoods of indigenous and other local communities.

In January 2022, an external Mid Term Review (MTR) of the project identified substantial changes in the main drivers of deforestation in the project landscapes (vis-a-vis those identified at project design phase) and recommended the project team to engage in an adaptation process, with a systems lens, thus presenting an opportunity for an application of the CALI methodology.

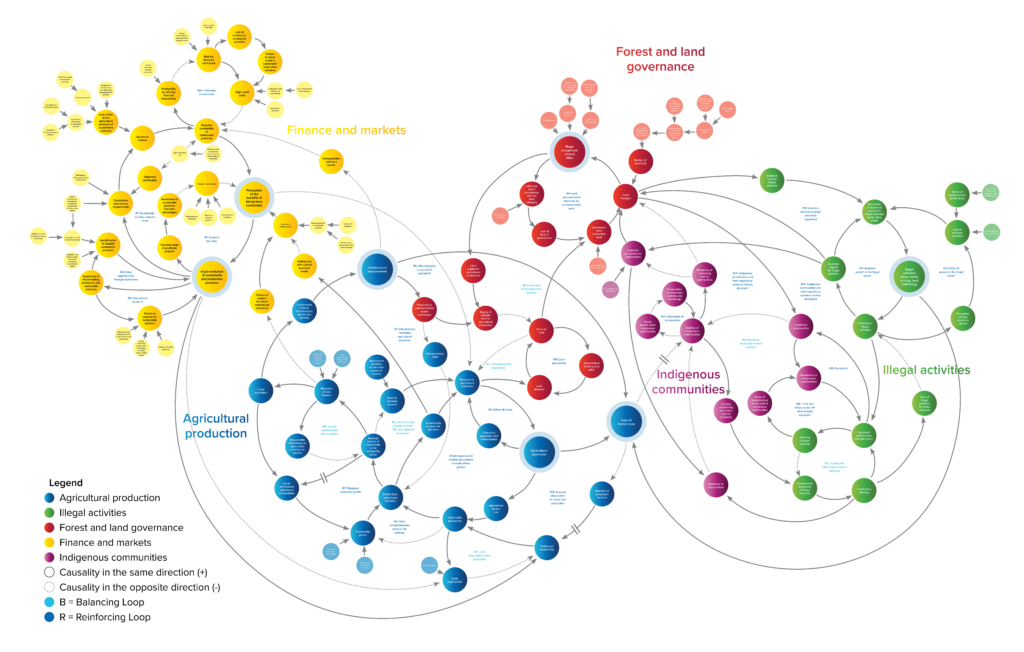

After having completed the preparation phase, the project team hosted a three-day systems mapping workshop in Pucallpa, in the Peruvian Amazon, with the support of Gian Wieck, founder of System Mapping Academy, and Dr. Malika Virah-Sawmy, founder of Sensemakers Collective, who served as facilitators. The workshop counted on the presence of the whole project team and key landscape stakeholders, including indigenous and other local community members, local authorities, and cooperatives. The process resulted in the development of a participatory, landscape System Map which was then validated with all workshop participants. Insights from the workshop were triangulated with studies and other relevant sources of information. For more information see this blog which provides a comprehensive recount of the development process from the perspective of the facilitators.

System Map developed as part of the application of CALI in support of the Sustainable Productive Landscapes in the Peruvian Amazon project, in Peru.

The System Map was then used to support further discussions on causality, resulting in a refined ToC for the project, and an enhanced suite of interventions. This process was led by the project team with the support of another consultant, following the remaining steps of the CALI methodology (steps 3, 4 and 5 presented in the section above).

Learnings from the Field

✔️ The participatory system mapping process enabled the project team to engage in reflection with a diverse set of stakeholders.

The UNDP Peru team began by identifying over 80 stakeholders, then narrowed it down to 40-45 through a prioritization activity and a specialized community database that contains actors who suffer or have key information about the phenomenon of deforestation. This process brought diverse levels of representation to workshops, including indigenous federations, regional governments, producer organizations, and various national entities serving different roles.

✔️ There is a strong appetite among local stakeholders for participatory exercises like CALI.

Interviews with participants from the system mapping workshop demonstrated a strong desire for increased participatory approaches for local interventions. For instance, since the initial workshop, indigenous organizations like the Confederación de Nacionalidades Amazónicas del Perú (CONAP) have continued to engage in participatory discussions on how to curb deforestation. Additionally, interviews revealed a desire for greater coordination between national and regional authorities.

✔️ The CALI methodology helped to bridge knowledge gaps and directly apply those learnings.

The CALI methodology effectively uses systems mapping to gather explanatory qualitative data that enriches the more descriptive, quantitative data that is often prioritized in development settings. While a necessary starting point, the latter often provides only limited explanatory insights into the why of a certain phenomenon – a bias that can hinder the ability to take effective decisions. In this context, CALI also serves as an entry point to introduce systems thinking and the adoption of collaborative, systems approaches in project interventions. This enhances the implementing team/s’ understanding of context and allows them to integrate new insights and ways of working into their strategies and intervention plans.

✔️ The implementation of the system mapping workshop elevated critically underrepresented perspectives.

The workshop engaged diverse stakeholders, with a particular focus on emphasizing the voice and perspectives of indigenous communities. This was done through dedicating the first day to an in-depth, preliminary discussion between the representatives of indigenous communities and the UNDP project team members, enabling participants to strengthen their understanding of each other's initiatives and perspectives. The subsequent day welcomed the rest of the stakeholders, fostering connections and mutual understanding between actors that do not often interact. This approach also allowed space for community members to share contentious yet crucial views such as the impact of illegal activities on local farmers and community insecurity. Though challenging, such open discussions can lead to transformative benefits for the community. These dialogues also expose decision-makers to diverse perspectives, aiding the development of more comprehensive and inclusive policies and interventions.

Must have mindsets for implementing CALI

Embracing systemic and adaptive thinking to navigate uncertainty and complexity

Successful implementation of CALI requires a mindset shift towards adaptability, embracing uncertainty and complexity, and the courage to listen and reflect and explore alternative paths as fresh insights emerge. At its core, CALI rejects a fixed route for programme and project implementation, and rather guides teams through a practical process to capture and navigate challenges and opportunities as they emerge. To do so, CALI integrates participatory systems mapping and data synthesis with landscape stakeholders and leverages collective sensemaking to surface practical and actionable insights for adaptation.

Skillful facilitation to support new community partnerships

Because interventions are informed by the system mapping workshop, it is critical for teams to skillfully facilitate sessions to ensure everyone is heard. Skilled external facilitators’ support ensures that the diverse perspectives represented are equally spotlighted. However, depending on who is present during the workshop, the insights shared are likely to be influenced. For example, if there are individuals who possess large amounts of power socially, politically, or economically, it is likely that their perspectives may be prioritized more than others with less positional power. Bringing individuals together with diverse perspectives to collaborate and share does not guarantee that power dynamics will not remain and influence or shape how decisions are made. As such, facilitators will play an important role in shaping the insights given they can guide the conversation and ensure that each person’s insights are discussed. Furthermore, strong facilitation enables strengthened relationships between the project team and key landscape stakeholders, as well as between stakeholders themselves. Improved engagement also contributes to legitimizing project initiatives and instills a sense of communal ownership, empowering these communities to take the reins.

Anchoring interventions in communal and localized knowledge

Stakeholder engagement and active listening are key factors for a successful implementation of CALI. Too often, in development projects, end-beneficiaries and project teams still have limited decision-making power or influence over a programme or project’s scope. The UNDP Peru team strayed from this typical scenario by organizing their system mapping workshops into 3-days engaging representatives of all landscape stakeholders, and prioritizing the voices and perspectives of indigenous community members. As applied by the UNDP Peru team, CALI challenges the traditional top-down way of decision making through empowering project teams, as well as frontline actors and communities.

Navigating change: your invitation to experiment with CALI

While CALI was created for landscape and jurisdictional approaches (LJAs) targeting deforestation, the methodology can be generalized to any other development project working in a bounded geographical area with a certain intent. Be that in a LJA or beyond, if CALI piques your interest, remember that early endorsement from leadership and donors is essential, and as such it is recommended to plan the assessments since project design. Ongoing adaptability needs a foundation of trust between donors, project teams and affected communities - and we hope this case study can serve as a useful tool for initiating and supporting these conversations.

We also believe there are opportunities for adapting and experimenting with CALI to ensure it adequately meets local needs. If you are interested in learning more about how the CALI methodology can be tailored to support your LJA or broader development project, do not hesitate to reach out to Andrea Bina, UNDP FACS Monitoring, Evaluation and Learning Specialist by writing to andrea.bina@undp.org.