Gardening a circular economy in Vietnam and the Philippines

A complex system of interactions – processes and behaviours, communities, institutions’ attitudes, cultural beliefs and personal dynamics – should enable a move towards a holistic change. But how?

The term circular economy first started to be formally used in an economic model in 1990, as an alternative to the linear take-make-dispose economic model. In a circular economy, waste is eliminated, resources are circulated, and nature is regenerated.

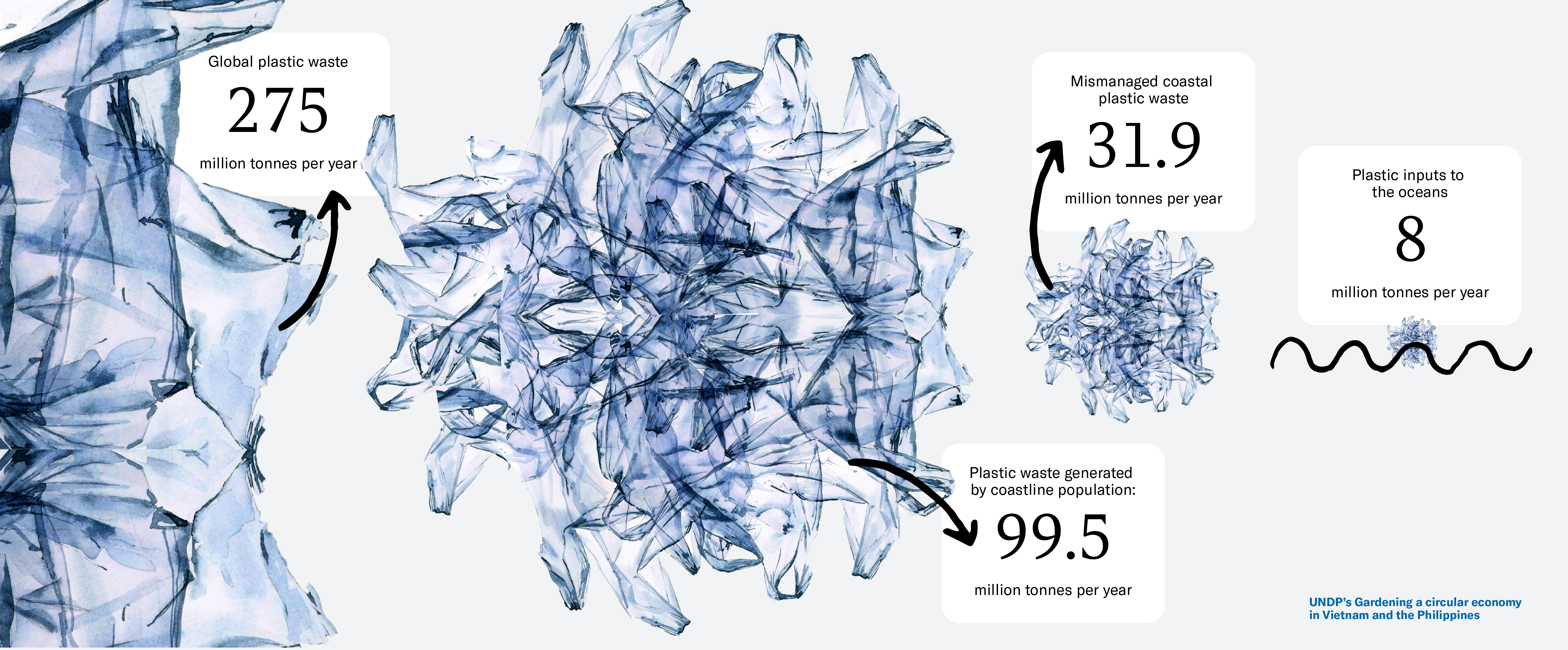

Every year, 8 million tonnes of plastic ends up in the oceans, with poor waste management by coastal communities and polluted rivers being the main causes of contamination. Incredibly, Asia alone accounts for more than 80% of the global leakage of plastic into the waters.

Waste management is unanimously considered a complex problem that requires long-term solutions. Some Asian countries have put in place considerable mitigation efforts into a transition to a more sustainable economic model, such as a circular economy. Yet, despite these attempts, actually implementing the structural transformations necessary is a struggle.

In Vietnam and the Philippines, the UNDP and its local partners are setting up a completely new approach aimed at nurturing a new economic model and reducing waste. This time, the changemakers refused the temptation to adopt quick short-term solutions. Instead, they switched to a listening mode: they used a variety of innovative methods to engage the community, which allowed them to begin to see things systemically.

As a result, unseen, underlying dynamics that affect waste management have been recognised, while alternative investment models that might enable a systemic change have been examined.

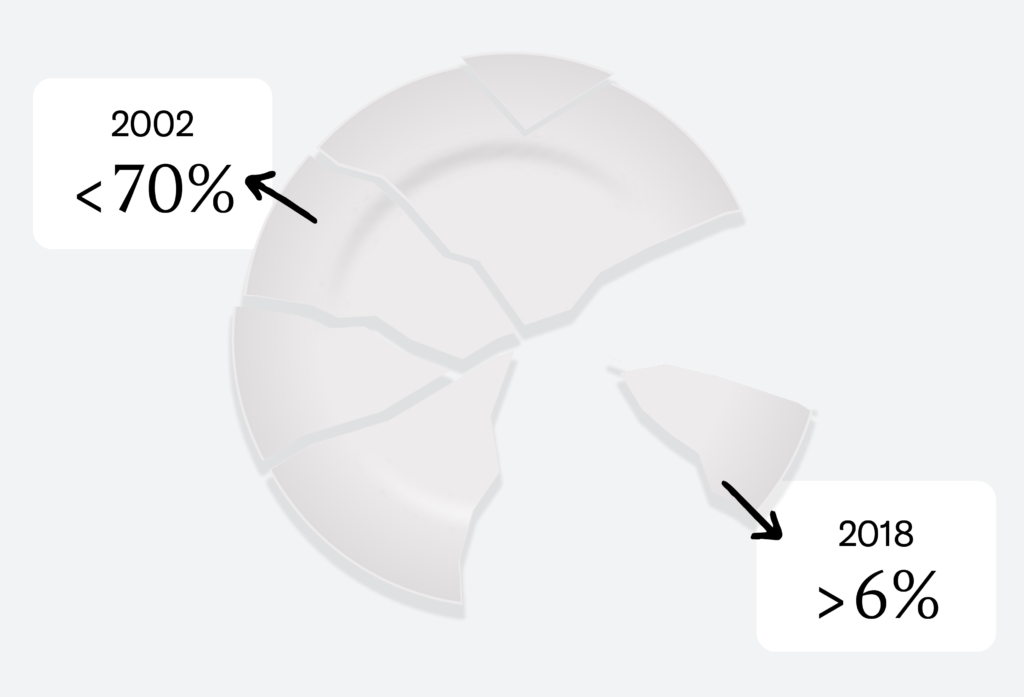

Since its economic “Doi Moi”, or revolution, in 1986, Vietnam has achieved enviably fast and consistent growth in its economy. From 2002 to 2018, poverty rates fell from over 70% to under 6% of the population.

The wicked issue of waste management in Southeast Asia

The Philippines. An archipelago of more than 7,600 islands – the second largest on the planet – that lies at the apex of the Coral Triangle and is a paradise for marine biodiversity: coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangrove and beach forests, fisheries, invertebrates, seaweeds and marine mammals.

The Philippines is also one of the fastest-growing economies in the Asia Pacific region. In the last 30 years, economic growth around the world has facilitated a remarkable reduction in poverty. Vietnam has similarly benefitted from rapid economic growth, which has transformed it from one of the world’s poorest nations into a lower middle-income country.

That overall progress, however, rests upon a flawed economic model. A take-make-dispose linear economy that fails to cope with the severe environmental impact generated by the extraction and processing of resources.

To give an example, the Philippines is sadly one of the main polluters of the marine environment globally. It has been recently estimated that 81% of ocean plastics come from Asian rivers; the Philippines alone contributing to around one-third of the global total.

The pathway of plastic waste into the oceans

Contrary to what those rates may suggest, Asian countries are not among the top producers of plastic waste. Filipinos produce just 0.07 kilograms of plastic waste per person per day, half of the per capita plastic waste in the UK. We have roughly the same numbers in Vietnam.

However, waste in these countries is often mismanaged – which is why such a large share ends up in the oceans. For example, in Asian coastline communities, plastic waste is often stored in open and insecure landfills, at high risk of leakage or loss, or it is discharged into bordering rivers and canals directly from households.

From engineering communities to gardening change

Bans on single-use plastics, public-facing awareness campaigns and extended-producer responsibility are all examples of approaches that seek to shift the burden of the waste issue onto producers. Incinerators represent a typical technical fix.

We can call them silver-bullet solutions: quick interventions that will have a certain impact while also appealing to political sensitivities. None of these approaches are wrong per se, yet none of them are completely sufficient in isolation either. They tend to ignore a lot of informal knowledge, like existing cultural norms or spontaneous dynamics within the communities.

As a result, these initial plans rarely survive the first contact with the local reality. In Vietnam, for example, people don’t want to appear in public handling or touching waste. Ignoring this important cultural information can easily ruin a municipal waste segregation project.

The UNDP has progressively abandoned the faulty idea of framing “plastic waste” as a mere technical or management problem. Rather, they switched to a much more nuanced understanding, where behavioural and cultural patterns rise in importance. Instead of attempting to engineer societies through silver-bullet projects, they have started gardening change: seeking to support, help and learn alongside citizens and local stakeholders as much as they can.

Let’s discover two stories from the Asian Pacific.

Pasig City is a highly urbanised city with a population of +800k people. The Pasig River runs through the city, connecting Laguna Lake, the largest lake in the Philippines, to Manila Bay in the Pacific Ocean.

Pasig City. Success story of engaging communities

Pasig City is one of the many independent city administrations in the central part of Metro Manila, Philippines. Among the mix of high-rises and lower residential buildings, the Pasig River flows. This river is known as one of the world’s top plastic polluters.

Much of the plastic litter comes from households; products being dumped directly into the river by those living nearby. That signifies poor waste-management infrastructure, a lack of material recovery facilities, and a lack of discipline of the people. What would a circular economy look like in this complex urban context?

Get closer to daily life to explore complex systems

The UNDP researchers adopted a novel “exploring mode” approach, and they engaged the community. A so-called rapid ethnographic research allowed researchers to get closer to the everyday life in the city, resulting in a significant amount of both qualitative and quantitative data.

The research was conducted in Pasig City from February to March 2021. Empathy interviews were held by a small team from the UNDP Philippines and supported by Pasig City Hall employees. Relevant data was documented through field notes, observations, interactions and conversations – as the research exploration was all taking place via an immersion in the actual city context.

Citizens thus helped researchers to read the complex context of Pasig City, and the inquiry revealed “unseen” aspects that are often missed through traditional data gathering, analysis and policy development: what people feel, think and do, and what their needs, wants and fears are.

Citizens also helped to capture the multiple possibilities of how they could implement a successful urban circular economy.

Portfolios of experiments

The ethnographic research is only the first stage of a more complex approach – the aim of which is to move the system of Pasig City towards a greener, circular economic model. Later stages will include the implementation of portfolios of experiments that work in unison to address multiple areas for change at one time: policies and regulatory frameworks, people’s behaviour and infrastructure.

A tale of two cities, or more

Pasig is not only one city. This is one of the unseen perspectives that has emerged from ethnographic research. The formal communities: the upper and middle classes living in fenced subdivisions, and the informal settlers living near the rivers and the canals, are two distinct groups within the Filipino urban context. Each of these “cities” within the city has unique characteristics and so requires different approaches when dealing with them.

It’s therefore important that the national government, civil society, private sector, and other sectors working on a circular economy framework should not parachute intervention activity ideas out to an entire city or region, but approach idea creation by engaging all the communities – both formal and informal ones.

For example, after incentivisation programmes were introduced in coordination with the local government unit, residential communities in the Philippines have started to take waste segregation seriously. When waste is perceived by people as a commodity that has a value (or can be exchanged with equal value), this encourages people to treat it differently. It enables paths for reuse and recycling.

Urban gardens and material-recovery facilities are nascent bottom-up solutions that can be transformed into a hub for citizen-driven policymaking, education, creativity and innovation. Systems do not change systems; people do.

When waste is perceived by people as a commodity that has a value (or can be exchanged with equal value), this encourages people to treat it differently.

A systemic investment approach for a circular economy in Vietnam

Vietnam’s waste management system is emblematic of the failure of the classic take-make-dispose model: valuable resources are literally burned or buried. This represents not only a loss of valuable resources, but also contributes to the spoiling of the environment.

Only 10-15% of the solid municipal waste in Vietnam is currently reused, with much of that recycling taking place in “craft villages” where the low technology processing techniques utilised create significant pollution of the surrounding environment, particularly from water run-off. This happens, for example, in Da Nang – a fast-growing city and touristic destination – where a large community of waste pickers has created a resilient informal economy around the dump.

In January 2022, the revised Law on Environmental Protection (LEP) came into effect in Vietnam. It represents the most significant modernisation of the environmental law regime in the country since 1993. The law highlights the responsibilities of ministries and localities to integrate a circular economy in planning strategies, development plans, waste management and waste recycling.

Vietnam’s attempt at long-term transformation

The case of Da Nang is quite illustrative of the set of problems that emerges when change-makers operate in very complex and unpredictable human systems.

The city has an excellent sustainable development plan, yet it is struggling to turn it into reality. The only dump in the city is filling up, and leaking litter jeopardises the beaches. As a result, the Government of Vietnam has announced its intention to move towards a circular economy in the waste management sector: the aim is to reduce leakage into the environment, especially of plastic into the waters.

Yet, there are scarce details about how this huge systemic change will be achieved, and how infrastructural investments will be financed.

A systems approach to investment for a circular economy

In Vietnam, the UNPD has explored the possibility of financing the transformation in waste management through systemic investments – multi-asset financing schemes that accommodate the uncertainty expected in such complex systems.

A UNDP local team engaged in interviews with national and local government, NGOs, private investors and other players in order to identify the potential plastic recycling value. And actually, it turned out that Vietnam’s waste management system is a favourable candidate for applying a systemic investment approach: a multi-asset systemic fund.

The investments within a transformative strategic portfolio may comprise assets beyond traditional debt and equity instruments, or a hybrid of the two. It may include grants as well as the diverse financial instruments common in blended finance transactions in the climate space (e.g. full and partial guarantees, first loss provisions). It may also comprise innovative financial instruments – which are in the early development stage – such as plastic credits, revenue- or impact-based bonds, and insurance products.

Case studies’ takeaways

- Through a rapid ethnographic research (empathy interviews) in Pasig City, Philippines, unseen aspects of waste management that are often missed through traditional data gathering, analysis and policy development, were discovered.

- By engaging all the communities, both formal and informal, waste segregation started to be taken seriously. When waste is perceived by people as a commodity that has value (or can be exchanged with equal value), this encourages people to treat it differently.

- In Vietnam, the UNPD has explored the possibility of financing the transformation in waste management through systemic investments – multi-asset financing schemes that accommodate the uncertainty expected in such complex systems.

- It turned out that Vietnam’s waste management system is a favourable candidate for applying a systemic investment approach: a multi-asset systemic fund.

Author: Giovanni Blandino

Illustrations: Ivana Cobejová

Infographics: Milk Studio

Photos: cover photo by P199, photo 2 – Shutterstock by MDV Edwards, photo 3 – Shutterstock by aldarinho

Sources:

1. Circular Economy in the City: A Rapid Ethnographic Research on Circular Economy in a Philippine Urban Setting.

2. The Tale of Four Elements: Nurturing a Circular Economy Portfolio

3. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean

4. Experimentation in action: the Good, the Bad, the Unexpected

5. Systems don’t change systems. People do.