Portfolios:

Governments, NGOs, organisations and agencies in development – we are all aware that traditional ways of “understanding problems” and “implementing interventions” are ill-suited for the times we are living in.

Even the tiniest change is faced with overwhelming obstacles and tangled up in messy contexts. We crave for substantial shifts, yet what we get is hasty actions whose results stall us even more.

It’s clear that no single method can bail us out. That’s why at UNDP’s Strategic Innovation Unit, we’re exploring portfolios of diverse approaches to development.

Together with organisations, policy makers and partners around the globe, we’re learning about how a combination of different modes of thinking can help us understand what’s really happening and build meaningful options for change.

Read more about our journey:

At the UNDP’s Strategic Innovation Unit, we are trying to challenge the status quo. The Unit was set up in 2020 to address and innovate the ways development practices work.

We’ve also been learning lessons from Covid-19: no ad-hoc solutions, such as a contact-tracing app, are alone going to improve our response to the pandemic; just as new bike lanes alone are not going to radically change mobility. Short-termism is simply not helping enough with the complex challenges we are facing.

Instead, we feel that more space is needed to accommodate reality, and to learn from our previous actions. We’ve recognised that the world is anything but predictable and certain – and accepting that was our first good step towards achieving change.

The day we embraced uncertainty and started to see things differently

Reframing the problem – a set of questions to ask for better understanding

- What has our attention, what doesn’t, and why?

- Where do we sit in relation to the problem, and what are we observing?

- What parts of the problem are we looking at, and what is outside the scope of our current perspective?

- Whose interests do these perspectives reflect and favour, and whose are left out and overlooked?

Complexity was first described by obscure physics in the 20th century. The main feature of the so-called complex systems is that their behaviour is really hard to predict: there are too many components, interdependencies and continuous interactions for the system to be linear and certain.

Decades later, it was recognised that complex systems science admirably describes how certain things work in reality: the human brain, tropical rainforests, climate, civilisations, cells, and so on.

We have learned through science that the world is messy, uncertain, unpredictable. And we feel the same applies when facing development challenges.

Take Da Nang, Vietnam – a fast-growing city aspiring to become the next top tourist destination. On paper, its sustainable development plan is excellent. Yet, there is a problem: the only dump in the city is filling up. Leaking liquids jeopardise the beaches, and thus the opportunities for tourism. An incinerator is planned by the government, but in the meantime, a community of waste pickers has created a resilient informal economy around the dump. As we keep looking at it, relationships, connections and interdependencies multiply: any intervention will impact the whole city at a greater economic and social level.

As we keep looking at it, relationships, connections and interdependencies multiply: any intervention will impact the whole city at a greater economic and social level.

Da Nang – as with many contexts we are working in – is a complex human system where consequences are far from predictable. So how do you act here, when using a development approach that takes predictability for granted?

Experimenting with a new approach that supports the long-term

We decided to try approaching development in an alternative way, using a new attitude that accepts uncertainty and unpredictability, and which is grounded on complex systems science – the portfolio approach.

In Da Nang, for example, we started to see things holistically: single ad-hoc solutions – an incinerator; a new policy fostering recycling – are not enough if we want the city to radically change towards a circular economy.

Most importantly, portfolios have room to accommodate learnings and failures.

Instead of funding short-term unrelated projects, we have deployed a portfolio of options: interconnected interventions which together can ignite a long-term transformation in the community.

Most importantly, portfolios have room to accommodate learnings and failures. They are not set in stone, they instead adapt actively to the changing context. And they do not funnel the possibilities into one silver-bullet intervention, they instead increase the options available to people living in a human system.

The portfolio approach enables us to spread the risks, rather than focus on “one big thing”. Basically, not putting all the eggs in one basket.

Project vs. portfolio. What’s the difference?

| Ordered, stable and predictable | Context | Uncertain, dynamic and unpredictable |

| To implement solutions to a clearly defined problem | Purpose | To learn about a complex issue, discover entry points and engage with the issue |

| Deliver pre-defined objectives. These do not change over time | Results | Not possible to define up front. Start out with a general direction |

| Known and readily available. Designed and implemented by the project itself | Solutions | Emerge from exploratory probes in the portfolio and sensemaking of activities in a wider context |

| Intervention consisting of pre-defined activities rolled out in a controlled environment | Intervention logic | Iterative experimentation (emergence) with a variety of interconnected interventions |

| Project board, annual meetings, reporting progress against pre-defined KPIs and assumptions | Governance | Frequent discussions with the board, government, funders… Uncertainty is communicated and accepted |

| Members operate within their separate areas of expertise under the guidance of a team leader | Team | Convenes, plans and delivers interventions in collaboration with a wide ecosystem of stakeholders |

| Prediction, quantifiable. Risks to be controlled and removed | Approach to risk | Unpredictable. Risk management through rapid adaptation |

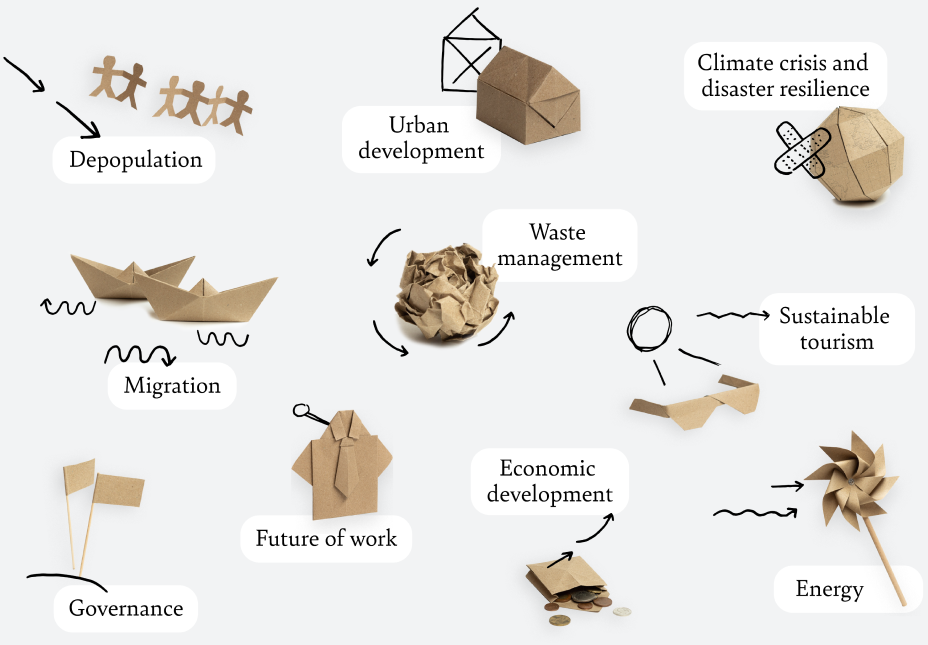

Complex areas in which we use the portfolio approach

Areas in which we apply portfolio thinking

- Depopulation and population movement causes

- Sustainable tourism and its impact on other fields

- Private sector, future of work and its character in different regions

- Waste management and its impact on health, environment, economic and social development

- Urban development respecting related issues such as migration, climate change and inequality

- Migration and resettlement in a development context

- Trustful governance and policy-making on multiple levels

- Climate crisis and disaster resilience

- Economic development of different communities

- Renewable energy

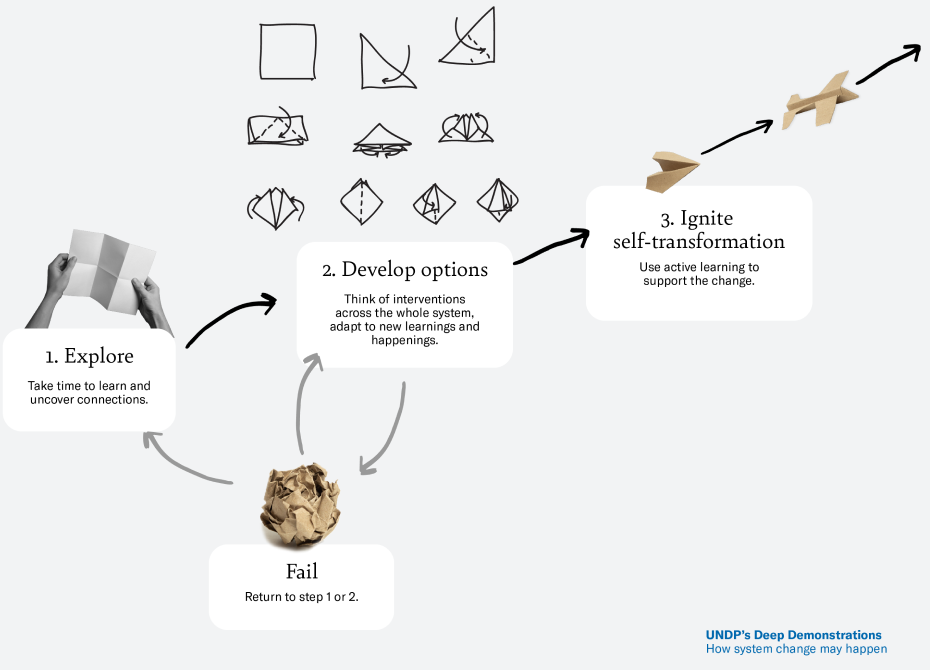

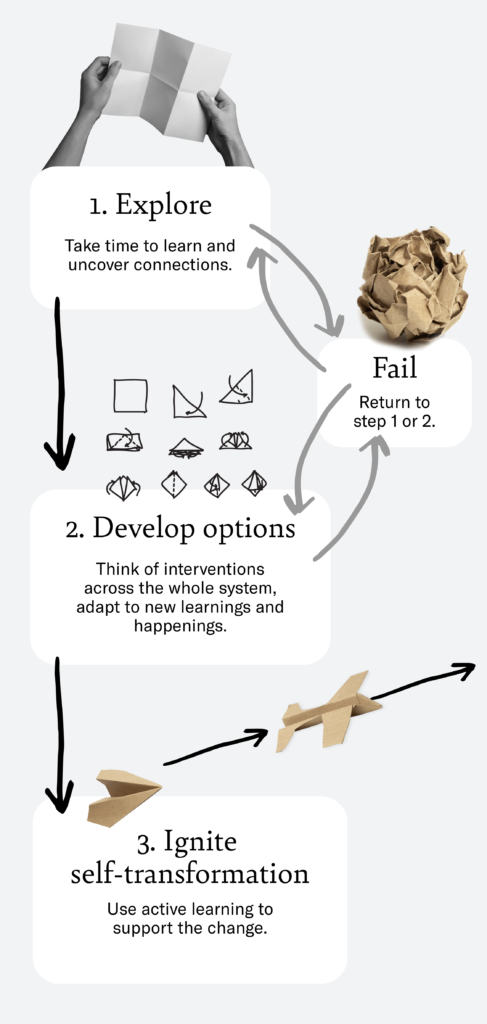

What are the key steps in creating change through options?

If you are thinking of the portfolio approach as a managing tool, you’re on the wrong track. Imagine instead interactive classes that enable learning about, and within, human systems.

The core of the classes is about designing a portfolio of options: interconnected interventions that – through active learning, failure and on-the-ground experience – help communities build up core abilities, stable relationships and inspiring narratives.

Portfolios enhance the adaptive capability of the system and work to launch a systemic change. We call it self-transformation: it makes communities more resilient and just, and it empowers societies to walk safely through turbulences and grow confidently towards the future.

How system change may happen

Human systems

Human systems are a farm, a village, a city, a border community, businesses in clusters, education structures, an entire nation. A human system is an incredibly complex system made of people, desires, money, power relationships, policies, needs, behaviours, cultural practices, images and beliefs. It is human, messy, uncertain. The portfolio approach helps us to see these contexts through the lenses of systems science.

1. Exploration

Explore, engage, see things systemically.

Do not run straight to the solutions – this should be repeated like a mantra. Take time to explore the context and see it through the lenses of systems science: this means you should engage with people within the community and gather information of different kinds, uncover connections and interdependencies, understand who needs to be there – partners, stakeholders, informal players – and start to build a shared vision.

2. Development of options

Create and deploy a portfolio of interventions; learn actively from the failures.

Similar to what happens in acupuncture, portfolios stimulate human systems – simultaneously – through different sensitive innovation points. If we want to help a city to be more sustainable, we should invest (concurrently) in interventions across the whole system: people’s behaviour, technology, markets, education, regulations and funding.

Interventions do not compete with one another, as is the case with the regular project approach, but instead interact and collaborate. Outcomes and objectives of the interventions – as with the portfolio itself – constantly adapt to new learnings, failures and happenings.

Funders are asked to invest not in individual projects, but in the portfolio itself, and in its ability to make change happen.

The purpose of the portfolio of interventions is twofold: to actively learn more about the context, and to trigger self-transformation within the system. From a funding point of view, it represents a real break away from the past. Funders are asked to invest not in individual projects, but in the portfolio itself, and in its ability to make change happen.

3. Ignition for self-transformation

Make sense, build narratives and core abilities, support systemic change.

Interventions deployed through the portfolio are something precious: they are experience on the ground, failure, reframing, new attempts. It is what we call active learning.

Active learning develops confidence and agency. It makes people understand challenges, imagining how they desire to transform their community. It assembles narratives: we call it sensemaking.

In addition to narratives, there is proven, sound experience. What has been learned through portfolios can be converted into policies, robust protocols, solid investments and stable cooperation among all the players. It is the act of building adaptive capabilities within human systems.

Deep demonstrations through the Innovation Facility – the way to apply the portfolio approach into reality

An important piece of the portfolio-approach puzzle is the “Deep Demonstrations”, which are the checks that enable us to learn how things will work in reality; in actual life.

We have probably talked in the abstract so far, but in fact, the portfolio approach is already happening: we have been trying it out on the ground, within cities, communities and countries.

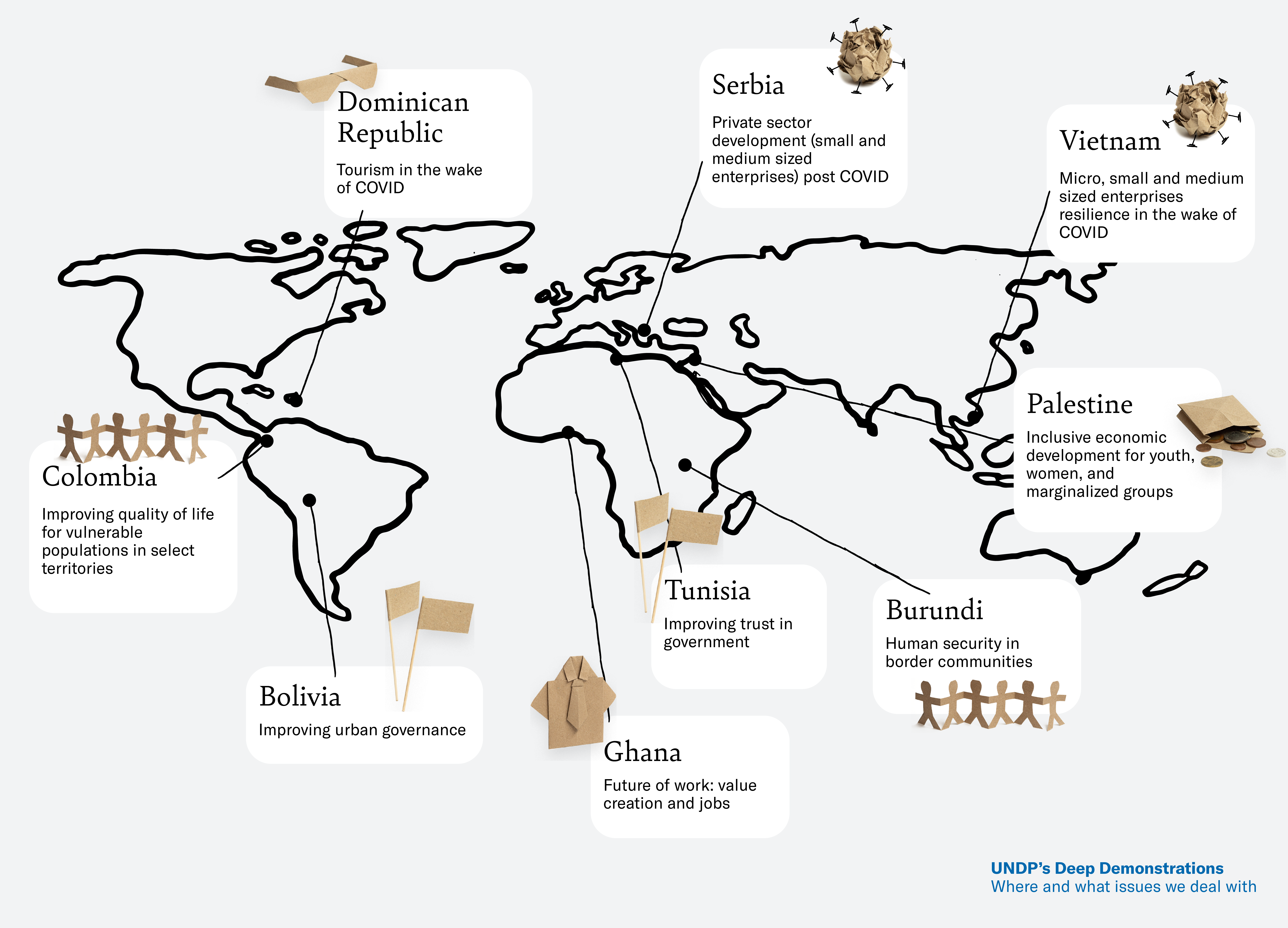

Since mid-2020, we’ve initiated deep demonstrations in 16 UNDP country office teams around the world, and another 25+ have applied the approach on a self-starter basis. Instead of going broad across many places, deep demos go deep in just a few, demonstrating the conditions required to affect system transformation in the field.

UNDP’s Deep Demonstrations

Where and what issues we’re dealing with

Three stories from the ground.

How deep demonstrations work in practice.

Further reading

Expanding options for Burundi border communities

Burundi is one of the smallest countries in Africa, but it has a considerable border area. Border communities are complex and fragile systems shuttering many returnees and refugees. Those communities are often economically disenfranchised, with poor levels of service delivery, inadequate infrastructure and elevated levels of insecurity and crime.

In mid-2020 we set up a deep demonstration to learn how to best support and enable positive self-transformation. We reframed our objectives: rather than “aiming to create employment opportunities for the poor” we set to “expand communities’ choices and opportunities”. We want to give people confidence in their actions.

We want to give people confidence in their actions.

A portfolio of interventions has been deployed, navigating the community towards a shared direction: women should be informed about rights and rules of border crossing to enhance their ability to move safely and confidently in daily activities; cross-border and community-based energy solutions help people in using local and liminal resources; better mobile services bridge public-service gaps between the centre and liminal spaces; public services make financial and social capital to encourage entrepreneurship amongst youth and more.

Exploring the strength and resilience of Palestinian grassroots economics

We started a deep demonstration in Palestine to support marginalised Palestinians and explore approaches that allow them to better absorb shocks and adapt during a crisis. In fact, the systemic exploration of grassroots economics revealed how SMEs and informal businesses have been incredibly resilient during the Covid-19 pandemic: they are agile and willing to adapt in the face of a crisis.

Engaging the great potential of the Palestinian diaspora, applying fair trade practices, improving brands through digital tools – some of the entry points of interventions we identified as opportunities for achieving systemic change.

We brought models and stories to the surface which can be used to leverage a more systemic transformation – where businesses can work together in clusters aggregated by values, strong social bonds and physical proximity. This could allow them to build an economy of scale in their production. Engaging the great potential of the Palestinian diaspora, applying fair trade practices and improving brands through digital tools are some of the entry points of interventions we identified as opportunities for achieving systemic change.

UNDP Bolivia’s journey into urban work in La Paz

In the deep demo in La Paz we wanted to understand the relationships and dynamics of work. We interviewed people from all walks of life and we learned a lot. We were eager to see this messy context through the lenses of systems science. Within La Paz’s working context, informality is no exception; it’s the main rule. Yet, under this informality we noticed a wealth of resources: dynamic women and young people, cultural heritage, resource flows, resilient businesses and energetic networks.

We crafted a portfolio of interventions that would expand options, especially focusing on women and youth.

Does this resonate with your own experience?

We’re ready to talk about our ways of observing, developing and starting change.

Deep demos are large-scale, open-air experiments – we’re trying things on the ground, we’re gaining experience and, of course, we are experiencing failures as well. We’re investing in exploration because we know that the traditional way of doing things in development is leading us nowhere.

Are you open to discovery? If you or your organisation is working on complex issues, the time has come to start looking at and framing things in a different way. Start a conversation with us today.

What we have learned:

Takeaways about Portfolios

- We believe that the portfolio approach is a good start in changing our ways of thinking. It’s already clear that short-termism got us stuck.

- The portfolio approach is a multiplicity of views that help governments and development collectives understand complex matters from within, systemically and holistically. It allows them to learn more about contexts and challenges, adapting over time to new inputs and failures.

- Deep demonstrations are reality checks for portfolios. With deep demos, we invest in developing new capabilities by doing; we work deep in a few places, instead of going broad in many.

- It is already happening. Nine countries are already actively using deep demonstrations in different fields: urban development, energy, future of work, depopulation, waste management and governance.