Observations:

Portfolio Approach

Observations are a live library of ideas to help you get unstuck. We talk to social development innovators, doers and thinkers and ask them to share their thoughts. These are some of their insights, served as small, refreshing nuggets of wisdom. Please, grab a bite and nurture your imagination!

Illustrations: Ivana Čobejová

Breaking the status quo, but how?

In development, there’s a strong shared feeling that business as usual doesn’t work anymore. More often than not, our solutions miss targets and break things further instead of fixing them. Baffled by the complexity of global challenges, development doers are left in despair.

But do we have an alternative? Can we resist the ever present temptation to perpetuate the status quo and continue our flawed job routines? What if we completely changed the way we perceive our challenges in the first place?

If these questions resonate, the following observations might be worth exploring – some of us are already on it.

Interconnections

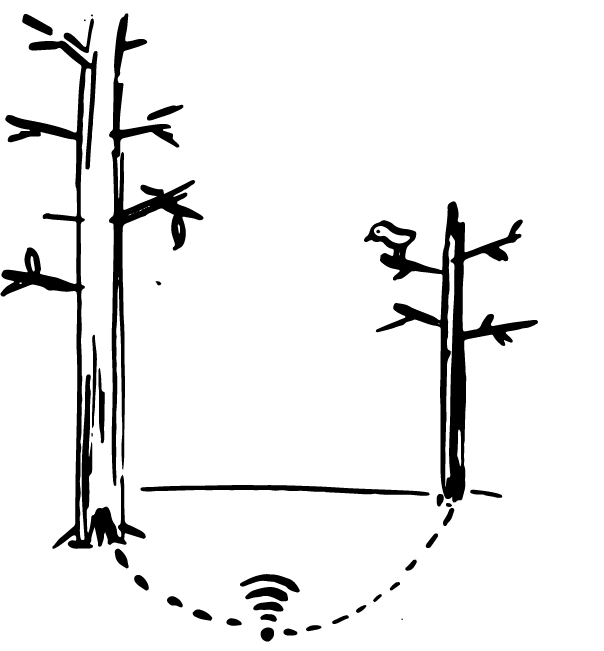

In the mountains of Eastern Oregon, the world's largest living thing on Earth can be found: a fungus that sprawls for the equivalent of 10 square kilometres.

To our anthropocentric way of thinking, mushrooms are very strange organisms. If you look at them underground, you'll see a network of tiny white threads which, collectively, constitute the mycelium – a genetically uniform organism with indefinite shape and size. In Oregon, scientists struggled with something as seemingly easy as finding where this creature ends.

Following the thin filaments of a mycelium, you can see them wrapping around or boring into tree roots. Individual plants connect to, and through, the fungus to other plants in the forest, to transfer water, nitrogen, carbon and other minerals. In a way, this is a “woodwide web” through which trees can “communicate”.

Imagine yourself tuning in with the context and, metaphorically with your hands in the mud, finding connections between projects, people, communities and needs. The game is to turn existing or planned interventions into a real, interconnected portfolio – a living organism in its own right.

In this sense, the work of biologists who patiently follow the hidden interconnections of a forest is not unlike that of development thinkers and doers. You just have to be willing to stick your hands in the mud.

Silver bullets? No, thanks.

Whenever we feel stuck in a corner, our instinct drives us to come up with fast, easy solutions: anything to fix the problem. Cassie Robinson, thinker and funding innovation expert, has artfully named this common attitude “the plaster syndrome”.

Indeed, mainstream culture seems to be obsessed with quick fixes. We can call them silver bullets or band-aid solutions, and they have one thing in common: they're hurried, short-term reliefs that cover up the symptoms, but do little to nothing to mitigate the underlying problem of a flawed system. They're just not sustainable. For example, an incinerator is a tech fix that may address a city’s waste problem, but as a single-point solution it does nothing to tackle the root causes.

Maybe the time has come to try something different. And ditch the silver bullets for good.

From silver bullets to portfolios of options

What does it look like to actually “do development differently”? There are already some points that may help community workers, innovators, doers and thinkers to climb the walls of a challenge: letting ideas work together, following hidden connections, framing root causes and – most importantly – offering people portfolios of possibilities instead of quick and fast solutions.

Will this be enough? How much does our mindset really have to change in order to accomplish things the alternative way?

And can we afford not to change?